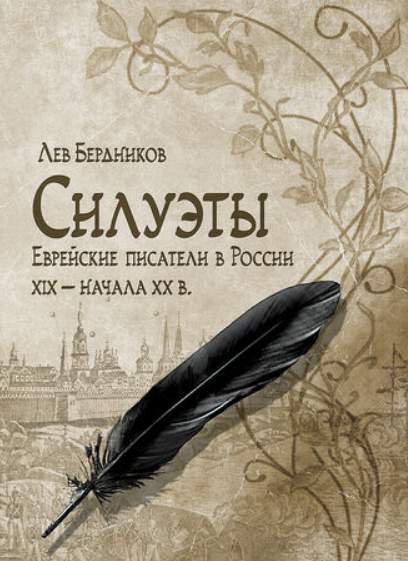

Lev Berdnikov, Siluety. Evreiskie pisateli v Rossii XIX – nachala XX v. (Silhouettes. Jewish Writers in Russia in the XIX

– beginning of the XX century). Ottawa: Accent Graphics Communications, 2017, 352 pp., ISBN: 9781546986362.

Lev Berdnikov is the author of several books and many articles on the history of Jews in the Russian Empire and Jewish-Christian relations. His new monograph focuses on the biographies and literary works of ten Russian-Jewish writers and poets.

These writers and poets lived in different times, had various political views, some of them converted to Christianity, other remained faithful to Judaism, however all of them had a genuine interest in Jewish themes. Most of these authors were Judeophiles and depicted with compassion the difficult life of Jews in the Russian Empire. They wrote about the restrictions and persecutions which were imposed upon Jews by the tsarist regime, about Jewish pogroms and Judeophobia. These authors hoped to gain the attention of Russian society to the discrimination against Jews and to improve the image of Jews in public opinion.

The Russian Jewish writer Lev Nevakhovich (1776-1831) was one of the first maskilim (adherents of the Jewish Enlightenment – Haskalah) in Russia. In his book Vopl' dshcheri iudeiskoi (Lament of the Daughter of Israel, St. Petersburg 1903) Nevakhovich wrote that Jews suffered for centuries from false accusations and the contempt of gentiles. He appealed in his works for Russians to be more tolerant toward Jews.

Leon Mandelstam (1819-89), like other Russian Jews maskilim, believed that the Enlightenment would improve both Russian and Jewish society. He wrote poetry in Russian, textbooks for Jewish schools and translated classical Jewish texts from Hebrew to German and Russian, and wrote publicist works in defense of the Jewish people. Mandelstam believed that Jews deserve equal rights and would receive them after ‘mergence’ (i.e. acculturation) with the Russian population.

Berdnikov wrote that the writer Abram Solomonov (1778-18??) was also a maskilim and quite a contradictory figure who simultaneously defended the Talmud as the basis of Jewish education and supported the idea of the assimilation of Jews in Russia.

Petr Weinberg (1831-1908) was an excellent translator, who introduced to Russian readers many works from foreign classical literature. Prominent among his translations were works on Jewish themes including Hebrew Melodies by Heinrich Heine, The Merchant of Venice by William Shakespeare and Torquemada by Victor Hugo.

Petr Weinberg’s younger brother Pavel was his complete antithesis. Pavel Weinberg (1846-1904) depicted Jews in his book Stseny is evreiskoi zhizni (Pictures from Jewish Life, St. Petersburg, 1874) and on the stage as pushy, annoying and ignorant provincials. As a comedian Pavel parodied the Jewish accent, laughing at Jews for their poor knowledge of Russian. He depicted Jews as cowards and greedy moneylenders. Such stereotypical Judeophobic depictions were a great success among some circles of the Russian public. Jews were insulted by such a distorted depiction and hated Pavel Weinberg’s book and his Judeophobic performances.

The Russian Jewish writer Victor Nikitin (1839-1908) had quite a dramatic biography: at the age of nine he was drafted into Russian Army as a cantonist and forced to convert to Christianity. (During the reign of Tsar Nicholas I, many nine - twelve year old Jewish boys were taken as cantonists, forced to convert and served for many years in the Russian Army). Years later Nikitin described the traumatic experience of Jewish children-cantonists in his book Mnogostradal’nye (The Sufferers). After his retirement from military service in 1869, Nikitin worked as a clerk in various state offices. The Jewish theme always remained in the focus of his attention. Nikitin wrote several sociological-historical works about Jewish farmers and Jewish prisoners, as well as his fictional stories.

The hopes of Jews maskilim to soon obtain in Russia equal rights were dashed by the pogroms of 1881-82 and the establishment of the policy of state antisemitism under the last two Russian Tsars Alexander III and Nicholas II. The reactionary Russian press blamed the Jews for all kinds of crimes and sins. In this political atmosphere, those who defended Jews also became the target of vicious attacks from reactionary circles.

Semen Nadson (1862-87) was a popular Russian poet who wrote only one poem on a Jewish theme Ia ros tebe chuzhim, otverzhennyi narod (I grew up shunning you, O most degraded nation, 1885), where he identified himself with Jews and showed great compassion for Jewish suffering. Semen’s Jewish paternal grandfather was converted to the Russian Orthodox religion, but his mother was from a noble Russian family. Thus, Semen could distance himself completely from Jewish problems, but he instead identified himself with Jews in times most difficult for them. His poem provoked the wrath of reactionary circles, who denounced Nadson and his poetry, but he received gratitude and support from Jews and liberals.

Semen Frug (1860-1916) was a very popular Russian Jewish poet during his lifetime and almost forgotten after his death. His poetry never was republished in the Soviet Union, because Soviet censors considered the poet as a “troubadour of Zionism.” But Frug’s poetry, as Berdnikov shows, was based mostly on Biblical motifs and depicted Jewish life in tsarist Russia.

The Russian Jewish writer Naum Kogan (1863-93) became well known after publication of his novel V glukhom mestechke (In a remote shtetl, 1893). Kogan was the first in Russian Jewish literature to depict the traditional life of Orthodox Jews in a remote shtetl.

Rashel Khin (1863-1928) was a Russian Jewish writer and one of the first feminist authors in Russia. She was the author of novels, plays and stories, several of which are devoted to Jewish themes and the struggle of women for emancipation. Rashel Khin also organized a literary salon in Moscow, where well-known Russian writers, poets, philosophers and lawyers read their works and had interesting discussions.

Today most of the writers, whom Berdnikov describes in his book, are semi-forgotten. However, their efforts to enlighten Jewish and Russian society did not vanish in vain. Their works impacted the views of the next generation of Russian Jewish intelligentsia and acquainted Russian society with the Jewish lifestyle, traditions and religion. Under the influence of these works, the Russian liberal intelligentsia acquired Judeophile ideas and supported Jews in their struggle for equal rights.

Lev Berdnikov effectively depicts in his monograph the political and social atmosphere in the country, and describes the heated debates about the status of Jews and their role in Russian society. His book is written in a scholarly-popular style and easy to read. But at same time his work has very valuable information about Jewish life in late Imperial Russia. Russian and Jewish historians, philologists and the lay audience will greatly benefit from reading this interesting work.

Victoria Khiterer, Millersville University